Each of us has his and her own quirks. But others may go too far – and more often than not, they are seen in people who are perceived to be as geniuses in their own field.

Perhaps it is not so surprising because there’s a “thin line between genius and insanity,” as one quote says. It’s no wonder that some of the greatest classical music composers – truly musical geniuses – had really extreme eccentricities, which may or may not have directly inspired or contributed to their work.

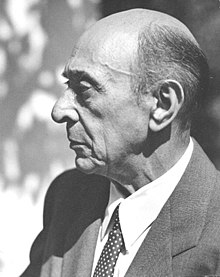

1. Arnold Schoenberg

Triskaidekaphobia (fear of the number 13)

Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg is widely regarded as one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was the creator of the twelve-tone technique, which led him to become recognized as one of the innovators of atonal music.

Having a highly superstitious nature, Schoenberg dreaded the number 13. He was born on September 13, 1874, and he considered the date of his birth as an evil omen. His fear of the number 13 was so irrational that when he noticed that the title of one of his works, “Moses and Aaron” had 13 letters, he omitted the second “a” in “Aaron” to make it 12.

On September 13, 1950, Schoenberg turned 76. A friend joked to him that the numbers “7” and “6” would add up to “13.” But for the composer, it was a bad joke that upset and depressed him, and he believed that he would not live past this age. And that happened. Schoenberg died on Friday the 13th — July 13, 1951 – a quarter before midnight.

The so-called “twelve-tone” technique Schoenberg invented was used for the first time in his 1923 publication of Five Piano Pieces, Op. 23 (although other twelve-tone techniques had been suggested, including one by Josef Hauer around the same time). The Serenade op. 24, the Suite for piano op. 25, and the Variations for Orchestra op. 31 were among a remarkable series of instrumental compositions Schoenberg produced that furthered the serial technique in the context of Baroque and Classical forms. The 1930–1932 opera Moses und Aron, which depicts the biblical story on a vast and intensely expressive musical canvas, is frequently regarded as a culmination of Schoenberg’s music of the preceding decade.

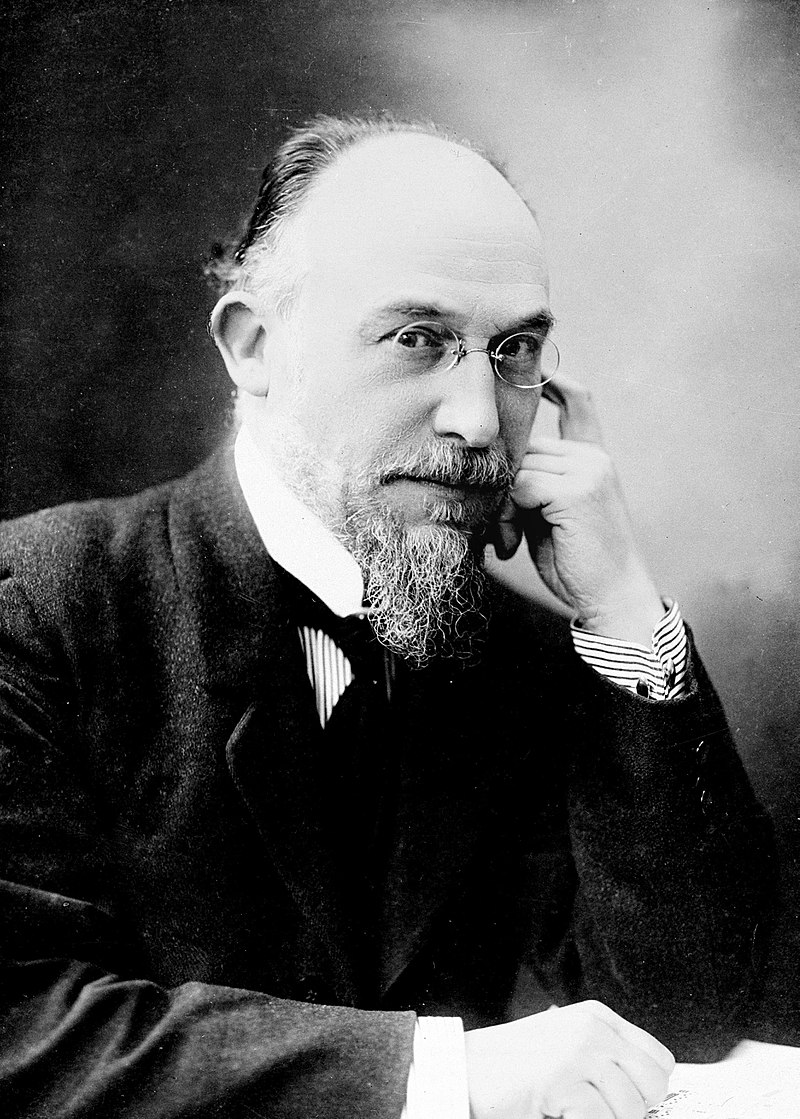

2. Erik Satie

“White food” diet (among many other eccentricities)

Erik Satie may be the most eccentric classical music composer that you would have ever come across. He was a 19th-century French composer primarily known for his famous three piano compositions, collectively called Gymnopedies. But he also composed pieces with weird, comical titles, such as Véritables Préludes flasques (pour un chien) (“True Flabby Preludes for a Dog”) and Embryons desséchés (“Dessicated Embryos”).

The music of Erik Satie is best described by what it isn’t rather than by what it is.

He wrote anti-emotional, anti-virtuosic, and anti-Wagnerian music as a contrarian, effectively rejecting all of the major trends in 19th-century classical music and blazing a new path for modernism, perhaps unintentionally.

Despite being a musical iconoclast and supporter of modernism, Satie showed a strong aversion to technological advancements like the telephone, gramophone, and radio. He didn’t make any recordings, and as far as is known, he only ever made one phone call and listened to one radio broadcast (of Milhaud’s music).

Despite his typically impeccable appearance, his room at Arcueil was described as “squalid” by Orledge, and after his death, scores of important works that were thought to be lost were discovered among the accumulated trash. He lacked financial acumen.

He was not much better off when he started to earn a good income from his compositions because he spent or gave away money as soon as he received it. In his early years, he had relied heavily on the generosity of friends.

Although he liked kids and they liked him, he rarely had easygoing relationships with adults.

As you might expect of Satie, he had his shares of his own weirdness. He owned twelve identical gray suits, but he would wear only one again and again until it wore out, after which he would wear another one. He hated the Sun and always had a hammer in his pocket to protect himself. He even founded his own church, the Metropolitan Art Church of Jesus the Conductor, with himself as its only member.

After Satie died in 1925, numerous letters were found at his home, which he had written to himself. One of these letters described his diet, which was no less weird – consisting of nothing but white foods: eggs, coconuts, sugar, shredded animal bones, cream cheese, rice, and so on.

Listen to Satie’s “Gymnopedies” piano suite below:

3. Richard Wagner

Cross-dressing and daily enemas

The great German Romantic composer Richard Wagner suffered from erysipelas, a type of cellulitis. This condition led him to painful and terrible rashes. He attempted (although unsuccessfully) to treat this condition with enemas, which he administered to himself twice daily. It may have been the reason for his predilection towards cushions and satin robes.

However, Wagner’s letters to his milliner (hat-maker) give hints that he was most likely a cross-dresser. Many of his letters include requests for “graceful costumes” with lots of lace and other feminine designs, and usually in pink. These dresses were for his wife Cosima (Franz Liszt’s illegitimate daughter). But Cosima, a diarist known for writing with great detail, never mentioned them in her accounts.

When Wagner died of a heart attack in Vienna in 1883, at age 69, he was reportedly dressed in a pink wedding gown, according to rumors.

Wagner was divisive during his lifetime due to his operas, writings, politics, beliefs, and unconventional lifestyle. After his passing, there has been ongoing discussion about his concepts and how they were interpreted, particularly in Germany during the 20th century.

Wagner’s anti-Jewish writings, such as Jewishness in Music, fit into some 19th-century intellectual currents in Germany. Wagner had Jewish friends, colleagues, and supporters throughout his life, despite his highly publicized views on the subject. There have been numerous claims that Wagner’s operas contain antisemitic stereotypes.

Until his final years, Wagner’s life was characterized by political exile, turbulent love affairs, poverty and repeated flight from his creditors. His controversial writings on music, drama and politics have attracted extensive comment – particularly, since the late 20th century, where they express antisemitic sentiments. The effect of his ideas can be traced in many of the arts throughout the 20th century; his influence spread beyond composition into conducting, philosophy, literature, the visual arts and theatre.

Listen to Wagner’s music below:

4. Anton Bruckner

A love for counting and skulls

Move over, Count Dracula! Austrian composer Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) suffered a particular kind of obsessive-compulsive disorder, called “numeromania,” which is an obsession with counting anything. He carefully maintained lists of how many “Hail Mary”s or “Our Father”s that he read out every night. As you might expect, his obsession with numbers extended to his work. For example, his finished scores and other works reflect this obsession with musical proportion: each bar is numbered, in units of 1 to 4, 1 to 8, 1 to 12, and so on, sometimes together with detailed harmonic analyses.

Even a lot weirder, Bruckner also had a morbid fascination towards skulls – in particular, skulls of dead composers. In 1888, he was there when Franz Schubert’s remains were exhumed. Bruckner seized Schubert’s skull and cradled it in the same manner that he did to Beethoven’s skull some years before.

Also, despite never having pictures of his mother when she was alive, Bruckner reportedly paid someone to take a picture of his deceased mother, which he then proudly displayed in his classroom. Additionally, it has been reported that he asked to see the skull of Emperor Maximilian, who was executed in 1867. Strangely, Bruckner’s obsession with death was the driving force behind the eerie, frequently dehumanizing orchestral landscape in sound that made him so successful.

Bruckner was well-known throughout Vienna for his peculiar obsession with teenage girls, to whom he made advances throughout his entire life. He tried to propose marriage to several teenagers, despite the fact that the majority of the girls he was interested in were typically half his age. Even going so far as to propose to one of his daughter’s teenage friends, the cantata “Entsagen” was written in anguish when she turned him down. A teenage girl was once very close to becoming his wife, but the engagement fell through when she refused to become Catholic. Even after turning 70, this obsession persisted.

5. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Fart jokes and cat sounds

Mozart is everybody’s idea of a child prodigy and musical genius: he composed his first piece when he was only five years old; at six, he performed before imperial courts; and at 11, he wrote and performed his first piano concerto. He composed many of his best-known concertos, symphonies, operas, and parts of the now-famous Requiem, which was left unfinished due to his untimely death at age 35.

Much has been said about Mozart’s personality as a “party person” and his fascination with scatology – that is, farting and pooping. In one of his funnier notes, Mozart recalled that there was a stinky odor entering the room. When his mother suspected that he was the one who farted, Mozart put his finger inside his rear and then sniffed it to confirm that she was right. He even composed a canon called “Leck mich im Arsch” (“Lick me in the arse”), which is thought to be a party piece that he wrote for his friends.

Mozart had a soft spot for all animals in addition to his love of music. As a result, he owned a dog, a canary, a horse, and a starling.

It is easy to assume that he acquired the canary and starling as a means of fusing his love of music with his admiration for nature.

His most well-known pet, the starling, served as a frequent source of ideas for his brief melodic compositions.

Mozart wrote a poem as a tribute to his musically inclined starling after the bird passed away. He loved the starling so much that when it died, he buried it in his backyard.

Less known about Mozart is that he was also a cat person – he loved cats so much that he would mimic them. One time, he was rehearsing an opera with his singers. Out of boredom and restlessness, he suddenly jumped over tables and chairs, meowing and tumbling. He even wrote a piece, known in English as the “Cat Duet,” in which a woman replies to her husband’s questions but meows, until the poor guy has no other choice but to say “meow,” too.

Listen to Mozart’s “Nun liebes Weichben” (“The Cat Duet”) below: