From the first intrepid pioneers who took to the skies in their flimsy biplanes to the cutting-edge modern jet setters who continue to push the envelope of technology, British aviators have played a crucial part in directing the evolution of aviation. Explore with us the intriguing lives and accomplishments of some of the greatest British aviators and pilots in history. Whether you are interested in aviation or history or are just seeking some motivation, you will gain a new respect for the tremendous things that can be accomplished through bravery, determination, and talent after reading about these amazing people.

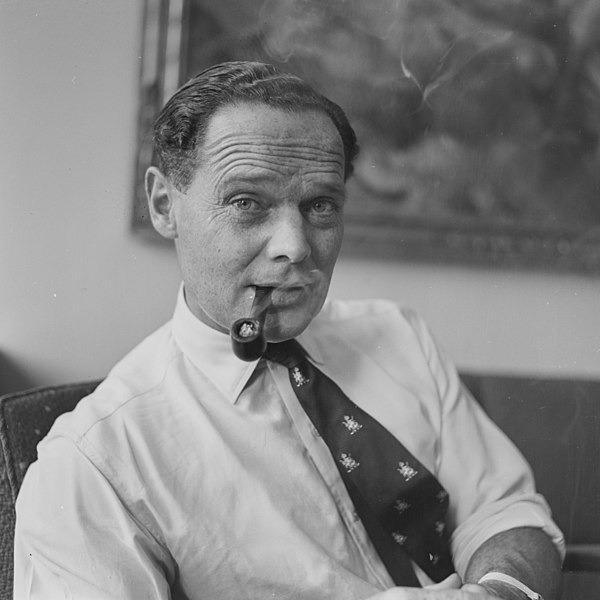

1. Douglas Bader

One of the most celebrated and motivational aviators in the history of the Royal Air Force, Group Captain Sir Douglas Bader is a name synonymous with the RAF. Bader lost both legs in an accident but continued to pursue his dream of becoming a pilot, ultimately becoming a celebrated ace during World War II.

Bader, who was born in London in 1910, enlisted in the Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1928 and was immediately impressed with his prowess in the air. But in 1931, tragedy struck when he lost both legs in a plane crash while performing aerobatics. Bader was determined to return to flying despite this heartbreaking setback, so he underwent intensive recovery and training. There were no rules that applied to his circumstances, but he passed his check flights and asked to become active again as a pilot anyhow.

When World War II broke out in 1939, Bader was able to rejoin the Royal Air Force and was issued a pilot’s license. The “Big Wing” experiments of Air Vice Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, which involved coordinating massive formations of fighters to target enemy aircraft, won Bader’s friendship and support.

In August 1941, Bader baled out over German-occupied France and was captured. He was disabled but attempted several break-outs before being sent to Colditz Castle’s POW camp. Bader stayed at the camp until April 1945, when the First United States Army freed the inmates.

Bader left the RAF after World War II and went back to work in the oil sector. He kept on being an example of perseverance and hope for disadvantaged people everywhere by sharing his story. Bader was honored as a Knight Bachelor in the Queen’s Birthday Honours for 1976 for his relentless advocacy on behalf of individuals with disabilities.

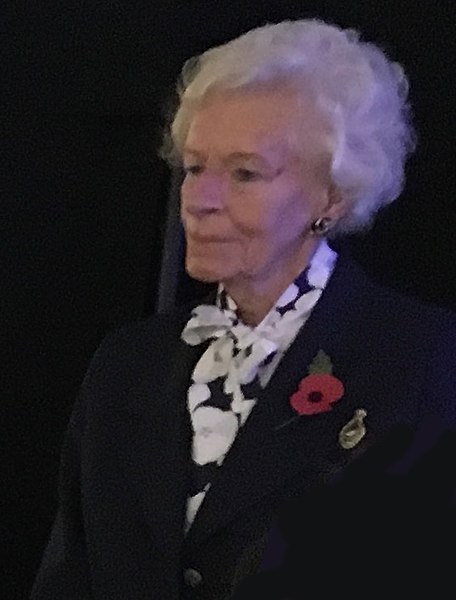

2. Mary Wilkins (Mary Ellis)

Mary Wilkins, a pioneer in British aviation, had a passion for airplanes from a young age. She lived in Oxfordshire, not far from an RAF base, and when she was eight, she talked her father into taking her for a pleasure flight in an Avro 504 with the Sir Alan Cobham Flying Circus. After that, she was determined to become a pilot. She took flying lessons at a Witney club when she was 16 and eventually received her private pilot’s license. Until the beginning of World War II, when civilian flying was forbidden, she continued to fly for fun.

As of 1941, Mary was serving out of a base in Hamble, Hampshire, as a member of the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA). During the war, she piloted over a thousand different planes, including the Harvard, Hurricane, Spitfire, and Wellington bombers. In addition to transporting planes from factories to Royal Air Force airfields, Mary also used these planes to move planes from airfields to the front lines.

Mary continued to transport aircraft for the Royal Air Force after the war, even though the ATA had been disbanded. In time, Mary rose through the ranks to become Europe’s first female air commandant and the manager of Sandown Airport. After twenty years at the helm of Sandown, she also established the Isle of Wight Aero Club. Mary promoted Vera Strodl, an ATA coworker and friend, to head flight instructor.

A Spitfire Girl: The Story of Mary Wilkins, One of the World’s Greatest Female ATA Ferry Pilots, was released by Mary Wilkins in 2016. Her example of overcoming obstacles to pursue their passions has encouraged many young women.

3. Arthur Whitten Brown

Scottish-American aviation pioneer Arthur Whitten Brown was born in Glasgow in 1886. Brown started his engineering career after moving his family to Stretford, Manchester. Brown joined the University and Public Schools Brigade (UPS), a group of aspiring officers, in 1914. He applied for a commission and was eventually accepted into the 3rd (Special Reserve) Battalion of the Manchester Regiment, where he served as a second lieutenant.

Brown was an observer seconded to the 2nd Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps, but his plane was shot down by enemy fire above Vendin-le-Vieil, France. He was transferred back to England for medical treatment, and on November 10, 1915, while on a reconnaissance flight near Bapaume in a B.E.2c (number 2673), he was shot down again. Brown and his pilot, 2nd Lieutenant H. W. Medlicott, were detained in Switzerland after being taken prisoner by the Germans. In September 1917, Brown returned home.

Brown joined Major Kennedy RAF of the Ministry of Munitions after a leave of absence. During this time, Brown became acquainted with and eventually married one of Kennedy’s daughters. After the war, Brown applied for a number of positions that would allow him to finally settle down and get married. He contacted several companies, including Vickers, which ultimately requested him to join John Alcock as the flight’s navigator for the planned transatlantic crossing.

From Newfoundland, Canada, to Clifden, Ireland, Alcock and Brown flew the first nonstop transatlantic flight aboard a modified Vickers Vimy in June 1919. They became household names after their flight, which took just under 16 hours. Alcock was knighted, and Brown was made a Commander of the British Empire, among other distinctions they earned. In 1928, Brown left aircraft behind and went back to his technical roots. He passed away in Swansea, Wales, in 1948.

4. Pauline Gower

Pauline Mary de Peauly Gower was a pioneering aviator and champion for women’s rights. She was born in Tunbridge Wells, England, on July 22, 1910, to Dorothy Susie Eleanor (née Wills) and Sir Robert Gower, MP. Gower grew up in Tunbridge Wells with her older sister Dorothy Vaughan at Sandown Court. She went to Beechwood Sacred Heart School and excelled in music and sports.

During World War II, Gower became active in the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA), utilizing her connections to suggest the development of a women’s section in the organization. Based in Hatfield, Gower developed a ferry pool in December 1939, initially consisting of eight female pilots, to ferry military aircraft from manufacturing or repair facilities to storage or active units. Joan Hughes, Margaret Cunnison, Mona Friedlander, Rosemary Rees, Marion Wilberforce, Margaret Fairweather, Gabrielle Patterson, and Winifred Crossley Fair were among the First Eight.

In the aviation industry, Gower was a prominent advocate for women’s rights and equality, and she continued to fly and promote women’s rights until her death. The British Library has audio of Gower talking about her night flight adventures over Kent, as well as her thoughts on women pilots. In 1950, she was awarded the Harmon Trophy posthumously.

5. Claude Grahame-White

Claude Grahame-White was a pioneer aviator and businessman in the field of motor engineering. He was born in Bursledon, Hampshire, England, on August 21, 1879. Grahame-White attended Bedford Grammar School before going on to become an engineer after completing his apprenticeship. He learned to drive in 1895 and went on to create his own motor engineering company. However, Louis Blériot’s flight across the English Channel in 1909 piqued his curiosity in aviation, prompting him to travel to France.

On October 14, 1910, Grahame-White flew his Farman biplane over Washington, D.C., landing on West Executive Avenue near the White House. Rather than being imprisoned, the newspapers praised him for his achievement.

Grahame-White is also credited with teaching some women to fly and establishing the Women’s Aerial League in 1909. Mrs. Winifred Buller, Lady Anne Savile, Eleanor Trehawke Davies, and suffragette leaders Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst were all members of this league. He founded a flying school at Hendon Aerodrome and trained Cheridah de Beauvoir Stocks, the second British woman to obtain a Royal Aero Club aviator’s license, in November 1911. Grahame-White gave H.G. Wells his first flight in 1912.

Grahame-White’s airport was given to the Admiralty during World War I and was finally taken over by the RAF in 1919. After a lengthy legal battle, the RAF purchased Grahame-White’s airport in 1925. After that, he lost interest in flying and settled down in Nice, where he passed away in 1959. His wealth had been accumulated through real estate development in the U.K. and the U.S.

6. Amy Johnson

Amy Johnson was born on July 1, 1903, in Kingston upon Hull, England. After attending an air show in 1928, she developed an interest in flying and began taking flying lessons at the London Aeroplane Club. She swiftly mastered the art of flying, getting her “A” pilot’s license barely six months after commencing her training.

Johnson made history in May 1930 when she became the first female pilot to fly solo from England to Australia. She piloted a de Havilland DH.60 Gypsy Moth biplane named “Jason.” The flight took 19 days and covered more than 11,000 miles. Johnson’s accomplishments established her as an international star, and she continued to set records over the next few years.

Johnson and her husband, Jim Mollison, achieved a new nonstop flying record from London to Cape Town, South Africa, in 1931. They flew a de Havilland DH.80A Puss Moth for the entire journey, which took just over four days. Johnson set a new solo record for flying from London to Cape Town in slightly under four days in 1932.

During WWII, Johnson worked as a ferry pilot for the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA). The ATA was in charge of transporting military planes from manufacturing and repair facilities to Royal Air Force stations. Johnson’s task was to fly the planes from the factory to the airfields, where pilots could employ them in combat. Johnson was flying a new plane from Prestwick, Scotland, to Oxfordshire on January 5, 1941, when she vanished over the Thames Estuary. The cause of her death is still unknown up to this day.

In conclusion, the stories of these British aviators and pilots are extraordinary. They were visionaries, risk-takers, and trailblazers whose contributions to aviation opened the road for modern air travel. Learning and understanding the struggles and triumphs of the pioneers of aviation helps us appreciate their contributions to the development of the said industry. These aviators and pilots are true heroes of the sky, and their stories continue to inspire and captivate us.