Muslim radicals assassinated Egyptian President Anwar Al-Sadat during a military parade commemorating the 1973 Yom Kippur War against Israel on October 6, 1981. The CBS News Bureau in Cairo tries to make sense of contradictory reports on whether Egyptian President Anwar Sadat had dead in the hours after the shooting while Sadat lay in a hospital. Due to this event, it is considered as one of the top political scandals of the 80s.

Background

Both President Anwar Al-Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin shared the Nobel Peace Prize in 1978 after the Camp David Accords. The following Egypt–Israel Peace Treaty of 1979, on the other hand, was met with opposition from Arab countries, notably the Palestinians. Egypt’s Arab League membership has been revoked. Yasser Arafat, the PLO’s leader, remarked, “Allow them to sign anything they want. False peace isn’t going to endure.” The Camp David Accords were utilized by different jihadist organizations in Egypt, including Egyptian Islamic Jihad and al-Jama’a al-Islamiyya, to garner support for their cause.

Egypt’s Islamists, who had previously supported Sadat’s efforts to incorporate them into Egyptian society, now feel deceived and have publicly advocated for the Egyptian president’s ouster and replace its political structure with an Islamic theocracy. Omar Abdel-Rahman, a preacher, subsequently imprisoned in the United States for his 1993 World Trade Center bombing, issued a fatwa condoning the assassination.

Internal unrest marred the final months of Sadat’s administration. He denied that the riots were sparked by internal concerns, thinking that the Soviet Union was enlisting the help of its regional friends in Libya and Syria to instigate an insurrection that would drive him from office. Sadat launched a severe crackdown after a failed military coup in June 1981, which resulted in the imprisonment of several opposition figures. He was killed “at the pinnacle” of his unpopularity in Egypt while maintaining high levels of support in the country.

Rectification Revolution

Islamists had benefitted from the “rectification revolution” and the liberation of activists imprisoned under Gamal Abdel Nasser earlier in Sadat’s administration. Still, his Sinai pact with Israel infuriated Islamists, notably the militant Egyptian Islamic Jihad. According to interviews and material obtained by writer Lawrence Wright, the organization was recruiting military commanders and stockpiling weapons in preparation for launching “a total takeover of the current system” in Egypt at the proper time.

Abbud al-Zumar, a military intelligence colonel, was El-chief Jihad’s strategist. He planned to kill the country’s prominent leaders, capture the army and State Security headquarters, the telephone exchange building. The radio and television facility, where news of the Islamic revolution will be aired, triggering a mass revolt against securocracy, as he predicted.

The arrest of an agent carrying critical information in February 1981 alerted Egyptian police to El-plot. Jihad’s Sadat ordered the arrest of about 1,500 individuals in September, including numerous Jihadists and the Coptic Pope and other Coptic clergy, academics, and activists of all ideological hues. All non-government media was also outlawed. The roundup missed a military jihad group commanded by Lieutenant Khalid Islambouli, who would assassinate Anwar Sadat the following October.

According to Tala’at Qasim, the former head of the Gama’a Islamiyya, who the Middle East Report interviewed, his group was known in English as the “Islamic Group,” who arranged the killing and hired the assassin or Islambouli, not Islamic Jihad. Two weeks before the assassination, members of the Group’s Majlis el-Shura or Consultative Council—headed by the infamous “blind shaykh”—were detained. Still, they did not reveal the existing preparations, and Islambouli was successful in assassinating Sadat.

The Death of President Anwar Al-Sadat

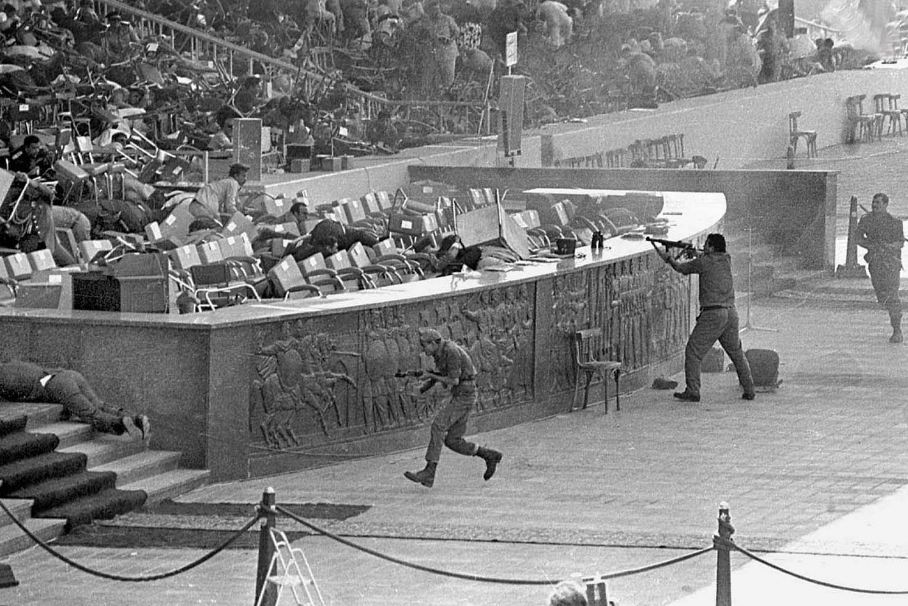

On the eighth anniversary of Egypt’s Suez Canal passage, a triumph parade was staged in Cairo on October 6, 1981. Due to munitions seizure laws, Sadat was protected by four levels of security and eight bodyguards, and the army march should have been secure. Egyptian Army soldiers and army vehicles hauling artillery paraded by while Egyptian Air Force Mirage planes soared overhead, disturbing the crowd. Lieutenant Khalid Islambouli’s assassination team was housed in one car. As the vehicle went through the tribune, Islambouli compelled the driver to come to a halt with a pistol.

The assassins dismounted from there, and Islambouli approached Sadat with three hand grenades hidden behind his helmet. Islambouli hurled all of his grenades at Sadat. Still, only one exploded, and other killers emerged from the truck. They were firing AK-47 assault rifles, and Port Said submachine guns into the stands indiscriminately until they ran out of ammo, then attempting to leave. People put chairs around Sadat after he was shot and had slumped to the ground, shielding him from the barrage of gunfire.

Hosni Mubarak, the Vice President, four US military liaison personnel, and Irish Defence Minister James Tully, were among the 28 wounded. Security forces were taken aback for a brief period, but they reacted in less than 45 seconds. Olov Ternström, the Swedish ambassador, escaped unharmed. One of the killers was killed, while the other three were injured and taken into custody. Sadat was taken to a military hospital, where eleven physicians operated on him. He passed away about two hours after arriving at the hospital. Sadat died of “severe head shock and internal hemorrhage in the chest cavity, where the left lung and main blood arteries below it were ripped,” according to the official cause of death.

Consequences

In Asyut, Upper Egypt, an insurgency was planned in response to the assassination. For a few days, rebels held the city, and 68 police officers and soldiers were slain in the battle. Government control was not reestablished until Egyptian paratroopers arrived. The majority of militants found guilty of fighting received standard terms, serving only three years in prison.

The assassins, including Islambouli, were prosecuted, found guilty, and condemned to death. Two army personnel were shot by firing squad, and three civilians were hanged on April 15, 1982.