According to a publicly released British diplomatic cable, in 1989, at least 10,000 people were massacred during the Tiananmen Square massacre in Beijing. This shocking event is one of the top political events in the 1980s.

The paper was made public 28 years after the military clashed with students at a pro-democracy rally in 1989.

Background

By the 1980s, China’s Communist Party officials had realized that traditional Maoism had failed. The Great Leap Forward, Mao Zedong’s fast industrialization and land collectivization strategy, had starved tens of millions of people.

From 1966 through 1976, the country was engulfed in the terror and chaos of the Cultural Revolution, an orgy of violence and devastation that saw young Red Guards ridicule, torture, murder, and even devour hundreds of thousands or millions of their fellow citizens. Traditional Chinese arts and religion were all but obliterated, and irreplaceable cultural relics were destroyed.

From 1966 through 1976, the country was engulfed in the terror and chaos of the Cultural Revolution, an orgy of violence and devastation that saw young Red Guards ridicule, torture, murder, and even devour hundreds of thousands or millions of their fellow citizens. Traditional Chinese arts and religion were all but obliterated, and irreplaceable cultural relics were destroyed.

China’s authorities understood they needed to make changes to stay in power, but what adjustments should they make? Leaders of the Communist Party were split between those who advocated for drastic reforms, such as a shift toward capitalist economic policies and greater personal freedoms for Chinese citizens, and those who preferred careful tinkering with the command economy and continued tight population control.

Meanwhile, with the Chinese leadership undecided on which path to pursue, the Chinese people found themselves in limbo between fear of the authoritarian state and a yearning to speak up for reform. They were yearning for change after the government-instigated disasters of the preceding two decades. Still, they were also aware that the iron hand of Beijing’s leadership was always poised to crush resistance. The people of China were waiting to see which way the wind would blow.

Aggravation of events

With Zhao Ziyang out of the country, extremists in the government, like Li Peng, used the chance to sway Deng Xiaoping, the Party Elders’ strong leader. Deng was recognized as a reformist who supported market reforms and more openness, but the hardliners overstated the students’ threat. Li Peng even informed Deng that the protesters opposed him personally and wanted his removal and the Communist government’s destruction.

Deng Xiaoping, clearly concerned, criticized the protesters in an editorial published in the People’s Daily on April 26. He dubbed the demonstrations dongluan, which translates to “tumult or rioting by a small minority.”

For fear of being punished, the students believed that if the demonstration were branded dongluan, they would be unable to put an end to it. Some 50,000 of them persisted in claiming that patriotism, not hooliganism, was the driving force behind their actions. The students were unable to leave Tiananmen Square until the administration reversed its characterization.

However, the editorial also caught the administration off guard. Deng Xiaoping had bet his and the government’s reputations on convincing the students to surrender.

The bout between Zhao Ziyang and Li Peng

When General Secretary Zhao Ziyang returned from North Korea, China was engrossed in the crisis. However, he believed that the students posed no serious threat to the government and attempted to calm the situation by asking Deng Xiaoping to retract the provocative editorial. However, Li Peng contended that taking a step back now would be a catastrophic display of weakness in governing party leadership.

By May 4, the number of demonstrators in Beijing had surpassed 100,000 for the second time. On May 13, the pupils took the next critical step in their lives. They announced a hunger strike to get the administration to withdraw the editorial from April 26.

On May 16, Soviet Premier and fellow reformer Mikhail Gorbachev came to China for discussions with Zhao in the middle of the upheaval.

A considerable force of international journalists and photographers arrived in the tense Chinese capital due to Gorbachev’s visit. Their stories sparked global outrage and demands for moderation and sympathetic demonstrations in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and ex-patriot Chinese populations in Western countries.

The Chinese Communist Party leadership was put under even more pressure as a result of the international outrage.

The onset of the Massacre

The People’s Liberation Army’s 27th and 28th divisions marched into Tiananmen Square on foot and in tanks on June 3, 1989, shooting tear gas to disperse the protestors. They’d been told not to kill the demonstrators, and most of them didn’t even have guns.

Local PLA personnel were regarded untrustworthy as possible protest sympathizers; therefore, the leadership chose these divisions since they were remote regions.

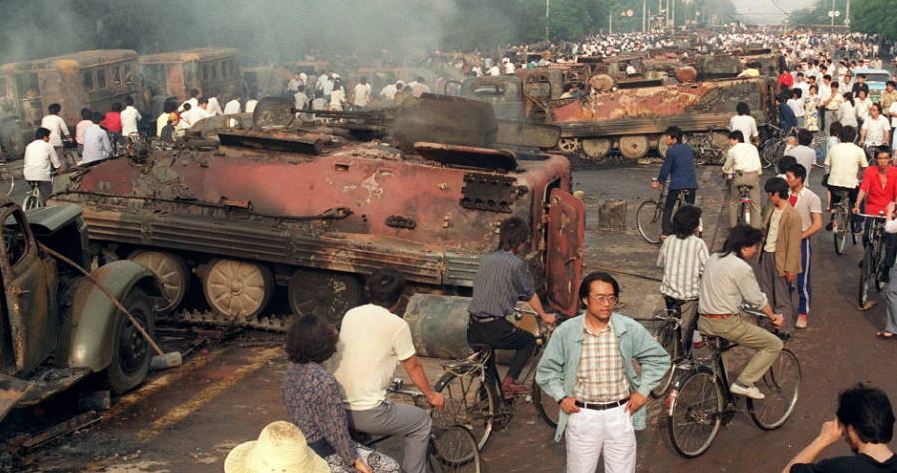

To oppose the Army, not only student protestors but also tens of thousands of workers and ordinary people of Beijing banded together. They built barriers out of burned-up buses, flung rocks and stones at the military, and even set fire to several tank personnel inside their tanks. As a result, the first victims of the Tiananmen Square Incident were troops.

Around 10:30 p.m., the PLA returned to the Tiananmen Square area with weapons and bayonets fixed. The tanks rolled along the street, shooting at random.

Rickshaw drivers and bikers dashed through the chaos, rescuing and transporting the injured to hospitals. A handful of non-protesters were also murdered in the ensuing mayhem.

The majority of the violence, contrary to common assumption, occurred in the districts around Tiananmen Square rather than in the Square itself.

Troops beat, bayoneted, and shot demonstrators throughout the night of June 3 and early hours of June 4. The tanks plowed through crowds, crushing people and bicycles beneath their treads. The streets surrounding Tiananmen Square had been cleared by 6 a.m. on June 4, 1989.

Aftermath

The Beijing Public Security Bureau issued an arrest warrant for 21 students identified as protest organizers on June 13, 1989. The Beijing Students Autonomous Federation, which played a crucial role in the Tiananmen Square demonstrations, was among the 21 most wanted student leaders. Despite the passage of time, the Chinese government has never removed this most-wanted list.

Survivors of the Tiananmen Square Incident had a range of outcomes. Some of the students, notably the student leaders, received comparatively low sentences. Many academics and other professionals who participated were banned and unable to find work. A considerable number of laborers and provincials were killed; exact statistics are unclear, as is customary.

June 4, 1989, was a watershed moment for the Chinese leadership. Reformers in China’s Communist Party were deprived of their authority and relegated to ceremonial posts. Zhao Ziyang, the former Premier of China, was never rehabilitated and spent the last 15 years of his life under house arrest.

Even decades later, China’s people and government have yet to address this historic and sad event. For those old enough to remember, the legacy of the Tiananmen Square Massacre festers under the surface of daily life. The Chinese government will have to confront this chapter of its history at some point.