Douglas Mawson and his team set out in the early 1900s to explore the vast, cold wilderness of Antarctica, embarking on a trek to the world’s most inhospitable territory. What began as a bold journey quickly turned into a heartbreaking survival story when Mawson’s team was rocked by an unanticipated tragedy that left them isolated and facing incredible obstacles.

Despite all odds, Mawson survived a grueling trek of hundreds of miles through some of the harshest conditions on the planet, demonstrating incredible resilience and determination. To this day, his extraordinary story of survival and endurance inspires and amazes others, reminding us of the great strength of the human spirit in the face of hardship. Join us as we delve into the astonishing survival story of Douglas Mawson’s Antarctic expedition and uncover the incredible feats of human endurance that were accomplished against all odds.

Who is Douglas Mawson?

Douglas Mawson was a well-known Australian geologist, Antarctic explorer, and scholar who was instrumental in the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Mawson was born in Shipley, West Riding of Yorkshire, on May 5, 1882, to parents Robert Ellis Mawson and Margaret Ann Moore. His family, however, immigrated to Australia when he was a child, landing at Rooty Hill, which is now located in Sydney’s western suburbs. Mawson spent his boyhood in this neighborhood before moving to the inner-city Sydney district of Glebe in 1893.

Mawson attended Forest Lodge Public School in Glebe, Sydney, where he obtained his primary education. He eventually finished his studies at Fort Street Model School, one of Australia’s oldest and most famous public schools. Mawson attended the University of Sydney after completing his secondary education to pursue a degree in engineering.

Mawson’s Interest in Antarctic Exploration

Mawson’s time at the University of Sydney was a watershed moment in his life, during which he developed a strong interest in geology and earth sciences. He received a Bachelor of Engineering degree from the university in 1902, but he continued to pursue his passion for geology, accepting a teaching job at the university as a lecturer in petrology and mineralogy in 1905.

Mawson’s interest in Antarctic exploration was aroused during this period when he became involved in the planning and preparation of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Nimrod Expedition. Mawson followed Shackleton on the trip from 1907 to 1909, and the experience shaped the rest of his life, prompting him to undertake his own expeditions and make substantial contributions to the area of Antarctic exploration.

The Nimrod Expedition

Mawson joined Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Nimrod Expedition as a geologist and member of the scientific team in 1907. The expedition’s goal was to explore previously unexplored parts of Antarctica and make fresh scientific findings.

Mawson had meant to stay for only one summer season, but Shackleton persuaded him to stay for a further year. This decision proved to be a watershed point in Mawson’s life, allowing him to take part in some of the expedition’s most significant accomplishments.

One of the Nimrod Expedition’s most significant achievements was the ascent of Mount Erebus, a still-active volcano that rises over 12,000 feet above sea level. Edgeworth David, Mawson’s tutor, and fellow expedition member Alastair Mackay were the first to reach the summit of this steep hill. This was no small effort, as the ascent was dangerous and took a considerable lot of skill, guts, and commitment.

Mawson and his colleagues, however, did not stop there. They continued their Antarctic investigation by traveling overland to the South Magnetic Pole. This was a rigorous and arduous voyage that had a physical and mental toll on the expedition members. Despite their difficulties, Mawson and his team became the first people to reach the South Magnetic Pole.

The Start of the Tragic Antarctic Trek

Following his experience with Shackleton’s Nimrod Expedition, Mawson declined an invitation to join Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra Nova Expedition in 1910. Instead, he elected to conduct his own Antarctic voyage, the Australasian Antarctic voyage, which set sail from Hobart, Tasmania, on December 2, 1911. The expedition’s goal was to conduct geographical exploration and scientific research, including a visit to the South Magnetic Pole. Mawson collected the necessary cash in a year from the British and Australian governments, as well as commercial investors interested in mining and whaling.

Captain John King Davis led the mission aboard the SY Aurora. On January 8, 1912, they arrived at Cape Denison in Commonwealth Bay and built the Main Base. A second camp was established on the ice shelf in Queen Mary Land to the west. The conditions at Cape Denison were exceedingly harsh, with persistent gusts that made the team’s work tough. Throughout the year, the average wind speed was around 50 mph (80 km/h), with some gusts reaching 200 mph (320 km/h). They built a hut on the rocky promontory and spent the winter amid near-constant blizzards.

During the voyage, Mawson wanted to pursue aerial exploration and took the first airplane to Antarctica, a Vickers R.E.P. Type Monoplane. However, the aircraft was damaged in Australia shortly before the expedition’s departure, and plans were changed so that it could only be utilized as a tractor on skis. Because the engine performed poorly in the cold, it was eventually removed and returned to Vickers in England. The airplane fuselage was abandoned, and bits of it were discovered in 2009 by the Mawson’s Huts Foundation.

The Death of Belgrave Ninnis

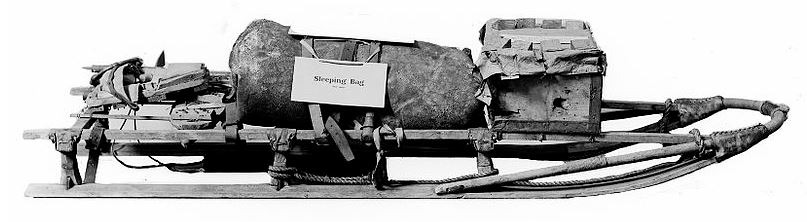

Mawson oversaw an exploration campaign involving five Main Base groups and two Western Base parties. On November 10, 1912, he was a member of the Far Eastern Party, a three-man sledding squad that set out east to survey King George V Land. Ninnis slipped through a crevasse while crossing the Ninnis Glacier after five weeks of progress and was never seen again. The party lost the majority of their supplies, including their six best dogs, leaving Mawson and Mertz with only one week’s worth of food for two men and no dog food.

After a brief service, Mawson and Mertz returned, sledded for 27 hours straight to get a spare tent cover, and fed the other dogs and themselves with their surviving sled dogs. They battled with a lack of supplies, and their meat was harsh and devoid of fat. They mixed dog meat with the stock of regular food, but the majority was served to the surviving dogs. The dogs ate the skin and crunched the bones until nothing was left.

The Death of Xavier Mertz

When Mawson and Mertz started experiencing hypervitaminosis A symptoms, they had no idea what was causing their condition. As they struggled to continue their journey back to the main base, their symptoms worsened. Mertz’s condition deteriorated rapidly, and his behavior grew increasingly chaotic. Mawson watched with horror as his companion’s mental and physical condition steadily deteriorated. Mertz lost consciousness and was unable to walk or even sit up on his own.

Mertz’s condition deteriorated over the course of the day. His skin went yellow, and he began to lose his hair and nails. He had diarrhea, and his body was covered with mucosal fissures. Mertz’s mental condition deteriorated as well, and he became increasingly delusional and angry. In one especially horrifying episode, he refused to acknowledge he had frostbite and proceeded to bite off the tip of his own finger. Mawson was forced to physically restrain him to prevent him from injuring himself or their tent further.

Despite Mawson’s best efforts to help his friend, Mertz’s condition worsened. He suffered from seizures before going into a coma and dying on January 8, 1913. Mawson was distraught by his companion’s death and struggled with his own physical and mental condition when he returned to the main base. It took years for the source of their disease to be found, and Mertz’s death might be traced to the high quantities of vitamin A in the husky liver that they had consumed.

Mawson’s Miraculous Survival and Return

After his journey to obtain food, Mawson continued his solo trip back to the Main Base. He had multiple near-death experiences along the road. During one of his sledding excursions, a snow bridge he was crossing over a crevasse collapsed, sending him and his sled plunging into the crevasse. He was lucky that his sled was trapped in the ice above him, stopping him from sliding farther into the crevasse. He used the strap that held him to the sled to climb out of the crevasse. He sustained severe injuries to his arm and knee as a result of the incident, making travel considerably more difficult for him.

Despite his injuries and the isolation, Mawson persevered, covering up to 32 kilometers every day. When he was crossing the icy salt lake, he almost drowned. His sled burst through the thin ice crust and began to sink. He had to hop off his sled swiftly and drag it out of the water barely in time. He was soaked and chilly as a result of the incident, and he had to construct a fire to dry himself and his stuff. Mawson also had to deal with terrible weather conditions, like blizzards and whiteouts, which made navigation difficult and travel practically impossible.

On February 8, 1913, Mawson landed at Cape Denison, only to discover that the Aurora had left a few hours earlier. Fortunately, Aurora’s crew had received Mawson’s wireless communication, and the ship was recalled. However, bad weather delayed the ship’s arrival at the Main Base until January 1914. Mawson and the six men who left behind to search for him were forced to spend a second year in Antarctica. Despite the difficulties, the expedition successfully charted the Antarctic coast and collected vital scientific data on the region. The Australasian Antarctic Expedition’s scientific successes and Mawson’s terrible ordeal cemented his reputation as a leader and explorer.

Mawson’s Post-Exploration Life

Following his marriage in 1914, Mawson was knighted and served as a major in the British Ministry of Munitions during World War I. In 1919, he returned to the University of Adelaide, where he was appointed professor of geology and mineralogy in 1921. During his stay at university, he made substantial contributions to Australian geology and conducted extensive research on the geology of South Australia’s northern Flinders Ranges.

Mawson coordinated and commanded the joint British-Australian-New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition from 1929 to 1931. The trip was a huge scientific success, and it resulted in the establishment of the Australian Antarctic Territory in 1936. Mawson also spent a lot of time studying the geology of Antarctica.

After retiring from teaching in 1952, he became an emeritus professor at the University of Adelaide. He died of a brain hemorrhage on October 14, 1958, at the age of 76, at his Brighton home. He had not finished editing all of the papers produced from his expedition when he died. Patricia, his eldest daughter, finished this painting only in 1975.

The narrative of Douglas Mawson’s Antarctic expedition is a monument to the strength of the human spirit and the unflinching determination to endure in the face of adversity. His extraordinary trip across one of the hardest environments on the planet, as well as the tragedies he encountered along the way, continue to inspire and intrigue people all over the world. By learning about his experiences, we can gain a better understanding of the strength and determination required to push beyond our limits and achieve the unattainable. Exploring Mawson’s narrative is a remarkable journey worth taking, whether you’re an explorer at heart or simply inquisitive about the accomplishments of the human spirit.