For generations, Chinese women endured the agonizing practice of footbinding, in which their feet were firmly bound to restrict development, resulting in misshapen and crippled feet known as “lotus feet.” Although it is currently illegal, this practice was originally considered a mark of beauty and social rank, and ladies who did not bind their feet were considered unattractive. But why did Chinese women participate in this agonizing tradition? Was it only a cultural standard, or did it have more profound historical and sociological implications? In this post, we’ll look at the fascinating and complicated reasons behind footbinding, as well as the painful process and the health issues it causes.

What is Footbinding?

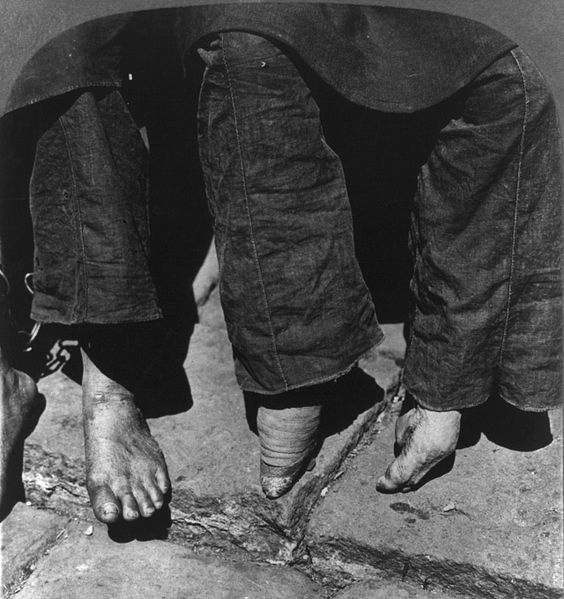

Footbinding, sometimes known as “lotus feet,” was a Chinese technique in which young girls’ feet were broken and firmly bound in order to modify their shape and size. The procedure was excruciatingly unpleasant and frequently resulted in permanent impairments such as reduced movement and constant discomfort. Foot binding was considered a prestige symbol and a mark of feminine attractiveness throughout late imperial China, despite the physical toll it imposed on women’s bodies.

Footbinding, despite its diminishing popularity, was nevertheless performed in some regions of China far into the twentieth century, particularly among rural and impoverished women. By 2007, just a few old Chinese ladies with shackled feet remained alive, providing a disturbing reminder of this cruel and humiliating practice.

Footbinding prevalence varied according to geography and socioeconomic status. Footbinding may have contributed to its popularity in some cultures by increasing women’s marriage possibilities. It is believed that during the nineteenth century, 40-50% of all Chinese women had bound feet, with the figure reaching over 100% in upper-class Han Chinese women. However, metropolitan and upper-class women abandoned the practice earlier than rural and lower-income women.

The Origins of Footbinding

The history of footbinding is veiled in mystery and folklore, with various legends concerning its origins. One of the most well-known stories is about the Southern Qi Emperor Xiao Baojuan and his beloved concubine, Pan Yunu. According to legend, Pan Yunu was known for her sensitive feet, and the Emperor commanded her during a barefoot dance on a floor covered with the design of a golden lotus, adding, “Lotus springs from her every step!” Although there is no proof that Consort Pan actually shackled her feet, this narrative may have given origin to the names “golden lotus” or “lotus feet” used to depict bound feet.

Another well-known anecdote featured Emperor Li Yu of the Southern Tang in the 10th century. Li Yu built a 1.8-meter-tall (6-foot-tall) golden lotus studded with precious stones and pearls and ordered his concubine, Yao Niang, to wrap her feet in white silk into the shape of a crescent moon and dance on the lotus’s points. Yao Niang’s dance was supposed to be so exquisite that other upper-class ladies tried to mimic her, and footbinding became popular.

Furthermore, several early references to footbinding occurred in poetry about 1100. Zhang Bangji’s discourse on footbinding, published shortly after 1148, emphasized that bound feet should be arch-shaped and tiny and that the technique was new, having not been referenced in any prior periods’ writings.

However, not everyone embraced the practice of footbinding, and by the 13th century, scholar Che Ruoshui had penned the first documented criticism of the practice, stating that young girls were subjected to suffering from tying their feet tiny, with no knowledge of the purpose of this.

The earliest archaeological evidence of footbinding may be found in the tombs of Huang Sheng and Madame Zhou, who died in the 13th century, with their feet tied with 1.8-meter-long gauze strips. Madame Zhou’s bones were so perfectly preserved that her feet fit into the small, pointed shoes she was interred with. It is worth noting that the form of tied feet discovered in Song dynasty graves, with the big toe turned upwards, appears distinct from subsequent centuries. The extraordinary smallness of the foot, known as the “three-inch golden lotus,” may have been a 16th-century evolution.

Footbinding During Post-Song Dynasty

Men had an odd tradition during the Song dynasty of drinking from a shoe with a little cup in its heel. This custom developed during the Yuan period when certain people would drink right from the shoe. This custom was known as “toast to the golden lotus” and persisted until the late Qing dynasty.

The Italian missionary Odoric of Pordenone was the first European to report the footbinding during the Yuan dynasty in the 14th century. However, no other Western travelers to Yuan China noted the practice, implying that it was not widely used at the time. The practice was supported by the Mongol rulers on their Chinese people, and it grew increasingly widespread among the elite households before spreading to the general populace.

Footbinding had become a prestige symbol during the Ming dynasty rather than a mark of the aristocratic class. Because it restricted the women’s movement, it contributed to a fall in the art of women’s dancing, and stories about women who were both dancers and courtesans became increasingly rare after the Song Dynasty.

Variations of Footbinding Practices

Footbinding was not performed evenly throughout China, with prevalence and severity depending on the area and social status. Footbinding at its most severe was observed in northern regions like Hebei and Shanxi, where feet were constrained to their smallest size. Footbinding, on the other hand, was less severe and less widespread in the southern provinces of Guangdong, Guangxi, Yunnan, and Guizhou.

Working-class women in Jiangsu purported to bind their feet at times, while some women were only temporarily bound and others were only bound till marriage. In the Eight Banners, Manchu women, like Mongol and Chinese women, did not tie their feet. The Hakka people were also unique among Han Chinese in that they did not use footbinding at all.

Footbinding became a distinguishing feature between Han ladies and Manchu or other banner women. Many Han Chinese women in Beijing’s Inner City did not tie their feet, and in the mid-1800s, 50-60% of non-banner women in Beijing had unbound feet. To mimic the stride of bound feet, the Manchus developed their own style of platform shoes. Footbinding was also practiced by Hui Muslims in Gansu Province. However, it was condemned by some Muslims as a violation of God’s creation.

The Process of Footbinding

Footbinding often began between the ages of four and nine before the arch of the foot had had a chance to fully mature. Binding was typically performed during the winter months when the feet were more likely to be numb, reducing the severity of the agony. Soaking the feet in a warm combination of herbs and animal blood, clipping the toenails back, curling the toes under, and then pushing them hard into the sole of the foot until they shattered were all part of the procedure. The arch of the foot was fractured violently, and the bandages were wrapped firmly in a figure-eight pattern.

The ties were tightened considerably more with each rebound of the girl’s feet, and this unbinding and rebinding routine was done as many as possible with fresh bindings. The girl’s injured feet required a lot of care and attention, including regular unbinding, bathing, toenail cutting, and kneading to make the joints and shattered bones more flexible. In addition, the feet were immersed in a mixture that caused any necrotic flesh to come off.

While the tied feet ultimately got numb, attempting to reverse the procedure was agonizing, and the form could not be altered without the woman suffering the same agony again. The process was performed by an elderly female member of the girl’s household or a professional footbinder, and it was preferred that someone other than the mother conduct it to guarantee that the bindings remained firm.

Health Problems Caused by Footbinding

Footbinding caused a slew of health problems. Infections were the most prevalent issue since toenails frequently became ingrown and infected, and toe injuries could not heal owing to poor circulation induced by the tight binding. In extreme situations, the flesh would decay, producing a terrible stench and increasing the risk of death from septic shock. It is estimated that gangrene and other illnesses induced by footbinding killed up to 10% of the girls.

Footbinding, in addition to infection, may cause bones to soften and toes to fall off if the infection spreads to the bones. Intentionally inducing infection by inserting glass shards or broken tile pieces was occasionally done to inflict damage and further tighten the binding. The foot bones were frequently damaged for years at the start of the binding, but they would ultimately mend. However, the mended bones were prone to rebreaking, particularly while the girl was in her adolescence and her feet were still tender. Because of their difficulty in balancing stably on their malformed feet, older women were also more prone to break other bones in falls.

Despite pictures, X-rays, and literary accounts exposing the deleterious consequences of footbinding in the twentieth century, the practice remained in certain rural regions until the mid-20th century. Footbinding’s impact may still be observed today in the feet of elderly ladies who experienced the treatment, many of whom have chronic pain and disability.

In conclusion, foot binding was a complicated and deeply rooted institution in Chinese culture that lasted for centuries. Its roots are buried in mystery and dispute, but its influence on Chinese culture, particularly on women, cannot be ignored. Despite the physical and psychological suffering felt by persons who had their feet tied, the practice survived owing to its association with beauty, prestige, and marriageability. Foot binding is now widely seen as a harsh and repressive practice, and the women who underwent it deserve our respect and appreciation for their fortitude and endurance. As we continue to study and learn from history, let us try to establish a more equal and just society for all women.