Prepare to add another name to your list of aviation legends! Blanche Stuart Scott, often known as the “Tomboy of the Air,” was a daredevil of the early twentieth century who paved the way for women in aviation. Despite numerous difficulties and gender prejudices, Blanche became the first woman in the United States to solo pilot a plane and even took to the skies in a 1910 display alongside famed flyer Glenn Curtiss. However, her narrative does not finish there! Join us as we delve into Blanche Stuart Scott’s adventurous life and uncover more amazing details about this incredible woman’s influence in aviation history.

Who is Blanche Scott?

In 1884, Blanche Stuart Scott was born into an affluent family in Rochester, New York. Her father, John Scott, was a successful entrepreneur who generated his wealth through the manufacturing and circulation of patented medicine. Despite her privileged upbringing, Blanche rejected the conventional path expected of women from similar social backgrounds. Blanche was captivated by automobiles, which were still a relatively new invention during her lifetime. When her father bought a car, she became one of the first people in Rochester to drive one. Due to the absence of age restrictions for driving during that period, Blanche had the opportunity to take control of a vehicle at a tender age.

Blanche’s love for driving led to her achieving local fame in Rochester. She even participated in some car races, where her fearless driving style made her a well-known figure. Despite this, her family disapproved of her “tomboyish” pursuits and sent her to finish school to learn the proper social graces expected of a young woman of her status. Blanche Stuart Scott’s love for machines extended beyond driving cars. She began driving at the age of 13 since there were no age restrictions or licensing requirements in the early 1900s. Blanche’s passion for driving became evident as she swiftly maneuvered through Rochester’s streets, sometimes causing quite a commotion. Her driving skills were so remarkable that the city council tried to ban her from driving, but their efforts were in vain.

Challenging Stereotypes and Breaking Gender Barriers

Blanche Stuart Scott’s interest in autos began at a young age, and she rapidly learned to drive. Despite her family’s displeasure, who wanted her to conform to the traditional standards of a young woman, Blanche pursued her passion for driving and even competed in several races.

Her driving ability drew the attention of Rochester’s municipal council, who attempted to stop her from driving. Blanche’s driving abilities, on the other hand, were so excellent that the council’s attempts were eventually futile.

Blanche set out on a transcontinental road journey across America at the age of 25 in 1910. Willys-Overland financed her trek from New York City to San Francisco, covering a distance of 5,500 miles in 68 days. Blanche drove an Overland roadster, which she affectionately dubbed “Lady Overland,” and completed the journey solely for her own enjoyment and educational value.

Blanche set out on her trip to disprove the assumption that women who owned cars were completely reliant on men or chauffeurs. Critics, however, questioned her capacity to complete the trek, citing the widely held assumption that women were incapable of handling anything mechanical.

Blanche, on the other hand, was eager to prove them incorrect and successfully finished the trek. Her journey also introduced her to the world of aviation, as she saw individuals fly for the first time. Initially, she thought they were “idiots,” but her interest was piqued, and she began to explore the possibility of taking to the skies herself.

Scott’s Start of Aviation Journey

Blanche Stuart Scott’s amazing road tour across America piqued the interest of Glenn Curtiss exhibition squad member Jerome Fanciulli. Fanciulli proposed teaching her to fly under Glenn Curtiss’ supervision, but Curtiss was apprehensive due to the potential negative attention he may receive for instructing a female student. Despite his doubts, he eventually accepted, and Scott became his first and only female trainee.

Curtiss was a hesitant and obstinate teacher, but Scott was desperate to learn. She was instructed in a one-seat plane known as a Curtiss Pusher, and her first training included very little ground instruction before she was left to figure out the rest on her own. They didn’t take you up in the air to train you back then; they just gave you some basic instructions, and then you were on your own. Scott, on the other hand, soon learned to pilot the plane by taxiing up and down the field, building confidence in her abilities.

Curtiss was still hesitant to let Scott fly alone, so he wedged a block of wood beneath the plane’s throttle pedal to slow her down and prevent her from attaining enough altitude to take off. A blast of wind pushed the plane off the ground on September 6, 1910, and Scott became the first American woman to fly. She remembered landing safely after her first flight, but she was resolved never to stay on the ground again. Her interest in aviation was piqued, and she went on to fly and break down barriers for women in the sector for many years.

Soaring to New Heights

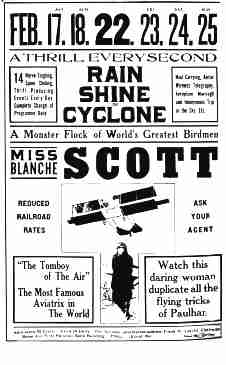

Blanche Stuart Scott immediately rose to prominence as the first American woman to fly. She began performing at air shows and exhibitions across the country, captivating audiences with her daring maneuvers and aerial gymnastics. In 1911, she joined the Moisant International Aviators, a group of pioneering aviators that toured the United States and Europe, performing death-defying acrobatics and feats of aviation.

Scott’s most famous feat was a loop-the-loop, which she executed in front of thousands of people at the Dominguez Air Meet in Los Angeles in January 1912. Many people felt that looping an airplane was impossible and that anyone who did it would almost certainly crash to their death. But Scott proved them incorrect by making a flawless loop in front of the audience.

Scott, in addition to her aerial achievements, made major contributions to the aviation business. She assisted in the design and testing of new aircraft, and she lobbied for the development of improved pilot safety measures. During World War I, she worked as a test pilot for the Army Air Service, helping to train new pilots and test new aircraft designs.

Despite her great accomplishments, Scott experienced enormous hurdles and discrimination as a woman in the male-dominated industry of aviation. She frequently had to fight for recognition and respect from her male coworkers, and she was sometimes refused opportunities because of her gender. Nonetheless, she persisted in pursuing her passion for flying, paving the path for future generations of female aviators.

From Daring Flights to License Restrictions

Blanche Stuart Scott continued to make her mark in the field of aviation after her historic flight in 1910. Her public performances attracted audiences, and she carried her abilities to Mineola, New York, where she became a member of Thomas Baldwin’s prestigious exhibition group. She faced a new obstacle as she operated the more difficult Baldwin Red Devil aircraft, demonstrating her unwavering determination and expertise.

Scott carved her name in the annals of aviation history once more in 1911 when she embarked on a stunning 60-mile long-distance flight. This groundbreaking achievement made her the first woman to accomplish such a feat. Seeking companionship and support, she relocated to Nassau, New York, where she joined the ranks of other great female aviators, including the famed Harriet Quimby.

Despite the accomplishments of her fellow female pilots, Scott met a roadblock. In contrast to her colleagues, she never got a pilot’s certificate from the Aero Club of New York. Glenn Curtiss and Thomas Baldwin both advised her against getting this certificate. As a result, she was forbidden from participating in Aero Club of New York-sanctioned activities, spurring her choice to travel to California.

During her time with Martin, Scott set a new record by becoming the first female test pilot in the United States. Despite her license restrictions, she continued to participate in activities that were not sanctioned by the Aero Club of New York. In a fortuitous turn of events in July 1912, Scott became a witness to the terrible airplane crash that killed her fellow aviator, Harriet Quimby. Rather than allowing the experience to break her spirit, Scott gained courage from her love of flying.

In 1913, she signed a contract with the Ward Aviation Company in Chicago and began a series of shows in the Midwest. Unfortunately, her plans were dashed on Memorial Day of that year when her Red Devil aircraft suffered a throttle wire failure and crashed. Scott has shown resilience and determination as she resumed her aerial hobbies after a year of recovery.

Retirement and Post-Aviation Career

Blanche Stuart Scott decided to retire in 1916 after a successful and groundbreaking career in aviation. Her decision was driven by the scarcity of chances for female engineers and mechanics and her growing dissatisfaction with the public’s macabre fixation with air catastrophes. Scott entered the entertainment sector with a desire to explore new frontiers, taking on various positions.

Scott’s post-aviation career took her into the realm of screenwriting, where she rose to prominence in the film industry. She contributed her creative talents to studios like RKO, Universal, and Warner Brothers, where she worked on various films. Along with her writing endeavors, Scott dabbled in radio, where she found success as a radio personality and even took on the role of radio station assistant manager. During this time, she acquired the moniker “Roberta” and began producing and hosting her own radio shows, demonstrating her versatility and adaptability in an ever-changing media world.

In a remarkable feat, Scott once again etched her name in the annals of history in September 1948, becoming the inaugural female passenger to soar through the skies aboard a jet aircraft. Chuck Yeager, a prominent United States Air Force Officer, extended the invitation and invited her to experience the excitement of flying in a TF-80C. This thrilling event was yet another exceptional feat in Scott’s extraordinary life.

Driven by her passion for aviation and possessing a wealth of knowledge about its rich history, Scott’s profound enthusiasm led her to assume the role of a special advisor for the Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base during the 1950s. During her tenure in this position, she was instrumental in collecting aviation memorabilia, amassing a stunning $1.25 million in priceless items. Scott, with her customary wit, referred to herself as “one of the world’s best chiselers,” emphasizing her foresight and resourcefulness in obtaining such a spectacular collection.

View this post on Instagram

Blanche Stuart Scott was an extraordinary woman whose accomplishments and contributions to aviation continue to inspire and impact people today. Blanche Stuart Scott’s tale is about more than simply one person’s achievements; it’s about breaking down societal barriers, questioning norms, and proving that everything is achievable with determination and desire. Her legacy continues to inspire and encourage people all over the world, urging them to follow their aspirations and realize their full potential.