In the vast tapestry of wine history, there’s a chapter that is always overlooked — the fascinating narrative of China’s role in shaping this timeless tradition. While wine may not be a necessity in Chinese culture as it did in other regions, its undeniable influence has been woven into the very fabric of Chinese life. Throughout history, the Chinese have crafted their alcoholic beverages primarily from grains, leaving a distinctive mark on the world of drinks.

History of Winemaking in China

The history of wine in China is a fascinating journey that stretches back thousands of years, intertwining with the nation’s rich cultural tapestry and diverse traditions. While wine may not have held the same prominence in Chinese culture as it did in some other ancient civilizations, its presence and influence have left an indelible mark on the nation’s heritage.

Ancient Roots: The Origins of Chinese Wine

The story of wine in China begins in antiquity, with evidence of alcoholic beverages made from wild grapes dating as far back as 7000 BC. Archaeological findings at the Jiahu site unearthed remnants of early alcoholic concoctions, hinting at the early experimentation with fermenting grapes to create a libation that delighted the ancient palates.

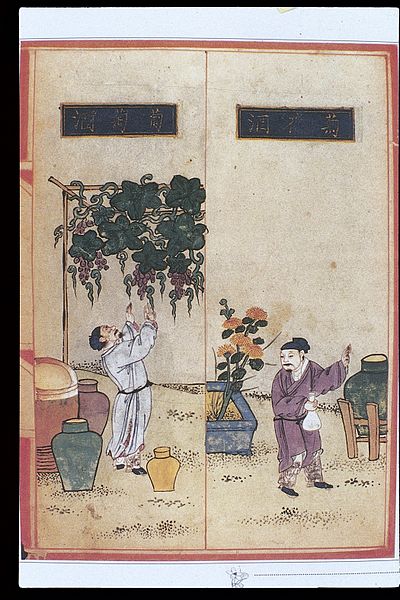

While wine consumption may have been relatively modest earlier, it wasn’t until the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD) that wine culture truly flourished. This golden age of Chinese history witnessed a renaissance of art, literature, and wine appreciation. The Complete Tang Poems, a vast anthology of poetic works from this period, features verses praising the allure of wine. One of the famous phrases, “qióng jiāng yù yè” or “jade-like wine,” vividly captures the elegance and enchantment that wine held in the hearts of poets and intellectuals.

In 1995, a collaborative Sino-USA archaeology team led by Professor Fang Hui embarked on an archaeological voyage near Rizhao. Among the many remnants of alcoholic beverages discovered at the sites—such as grape wine, rice wine, mead, and intriguing blends—seven ceramic pots stood out as vessels specifically used for grape wine. Evidently, the ancient Chinese enjoyed a diverse array of alcoholic creations, from sorghum, millet, and rice to the tempting flavors of lychee and Asian plum. If grape wine was consumed in Bronze Age China, it was most probably replaced in favor of alcoholic drinks made from the mentioned ingredients.

Wine in the Han Dynasty

In the 130s and 120s BC, a Chinese imperial envoy of the illustrious Han dynasty, Zhang Qian, forged diplomatic ties with Central Asian kingdoms, some of which produced the revered grape wine. The fabled grape seeds from the wine-loving kingdom of Dayuan (modern Uzbekistan) found their way to China during the Han era, eventually taking root in imperial lands near the bustling capital, Chang’an. This marked the start of grape cultivation on Chinese soil.

According to the Shennong Bencao Jing (an ancient work on materia medica from the late Han period), grapes were recognized for their potential in wine production. But during the Three Kingdoms era (220–280 AD), Emperor Cao Pi of the Wei dynasty made an intriguing observation, noting that grape wine possessed a delightful sweetness surpassing that of wines made from cereals and offered a smoother recovery after indulgence. Despite their cultivation in the northwestern region of Gansu for centuries, grapes were not utilized on a large-scale basis for producing wine, making it an exotic and relatively unknown elixir among the people.

Wine in Tang Dynasty

It was during the Tang dynasty that the consumption of grape wines truly came to flourish. Following the conquest of Gaochang, the fabled Silk Road, the ancient trade route connecting China to the West, played a pivotal role in introducing new varieties of grapes and winemaking techniques to China. Through trade and cultural exchanges with Central Asian kingdoms, Chinese envoys brought back grape seeds that flourished in the fertile lands near the capital city of Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an). The “mare teat” grape variety from these exchanges became highly prized, and the art of winemaking thrived.

Tang poets versified on grape wine, praising varieties from the “Western Regions,” particularly those from Liangzhou and Taiyuan in Shanxi, where the coveted “mare teat” grapes thrived. The renowned poet Wang Han penned verses that still resonate today. In the 8th century, his words captured a poignant scene in Liangzhou, where soldiers prepared to indulge in the finest wine from Evening Radiance cups, reveling in their triumphant battlefield victory. The poem eloquently portrayed their spirited celebration, but amid the merriment, news of a fresh enemy invasion arrived. Undeterred, these valiant warriors, both in ancient times and the present, unhesitatingly left the feast behind to confront the new threat. Wang Han’s poetic masterpiece struck a chord with the people, eventually becoming a beloved part of China’s wine culture.

Wine Culture in the Following Centuries

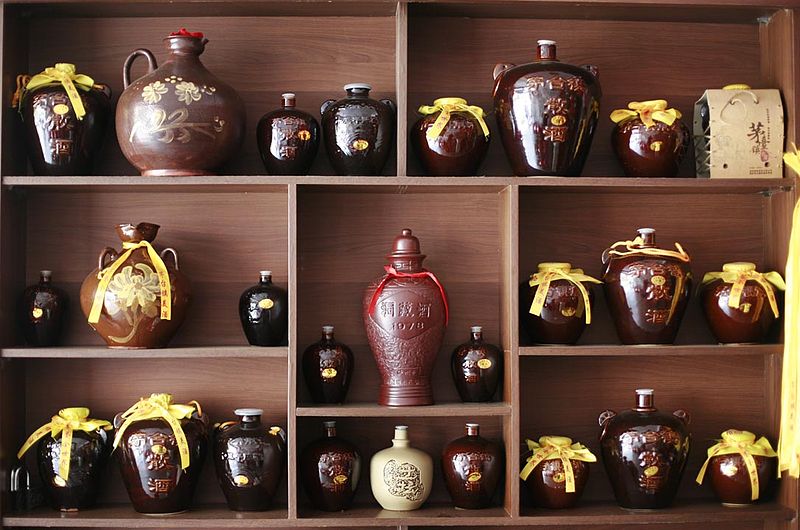

In the centuries that followed the Tang dynasty, China witnessed a continuation of wine culture, though it may not have enjoyed the same widespread popularity as other alcoholic beverages like huangjiu (yellow wine) and baijiu. Wine production and consumption remained regionally diverse, with areas like Gansu in the northwest becoming notable for grape cultivation. Throughout the Ming and Qing Dynasties, historical records indicate minimal progress in the wine industry’s growth.

The Emergence of Modern Wineries

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, China saw significant changes in its wine landscape. Influenced by foreign merchants and entrepreneurs, modern wineries began to emerge.

The “first modern winery” in China – the Changyu wine production company – was established in 1892 by a visionary overseas Chinese entrepreneur Zhang Bishi. Nestled near the vibrant port of Chefoo (now Yantai) in Shandong province, this winery marked a significant milestone as China’s foray into industrialized wine production began to take shape.

As the 19th century transitioned into the 20th, China opened its doors to European influences, welcoming diverse varieties of wine and innovative winemaking techniques from the continent.

French wine was the first foreign wine that entered the Chinese market. Taking advantage of the onset of Chinese economic reform in 1980, Rémy Martin ventured into China, establishing the pioneering joint-venture enterprise, Dynasty (Wang Chao) Wine Ltd., based in Tianjin. Over the years, the company flourished, boasting an impressive portfolio of more than 90 alcoholic beverage brands, garnering accolades both at home and abroad.

During the initial decades, the majority of the company’s products were exported overseas, owing to the limited disposable income of the local population. However, the tides turned after the turn of the millennium, as China’s economic boom provided its people with increased purchasing power, propelling the growth of the domestic market and fueling the surge in French wine’s popularity within the country. Simultaneously, other prominent wine companies, like China Great Wall Wine Co., Ltd., Suntime, and Changyu, also rose to prominence. By 2005, a remarkable shift occurred, with 90% of grape wine produced in China being consumed locally.

While China has an ancient tradition of fermenting and distilling various alcoholic beverages, the globalization of the wine industry has brought Chinese grape wine to the international stage. As the nation’s winemaking prowess gains global recognition, Chinese grape wines have started to make their way onto shelves in California and Western Canada, drawing mixed responses from critics. Some view this as a new frontier with the potential for exciting discoveries, while others acknowledge China’s ability to produce table wines comparable to those from established wine-producing countries. Notably, Inner Mongolia has ventured into producing organic wine.

By 2012, a handful of dominant companies, such as Changyu Pioneer Wine, China Great Wall Wine Co., Ltd., and Dynasty Wine Ltd., took center stage in the domestic wine production landscape. Overall, wine production witnessed a remarkable 15% increase in 2004, signifying the industry’s growing momentum. The wine market experienced a substantial 58% growth between 1996 and 2001, followed by an impressive 68% growth between 2001 and 2006.

Wine in China Today and in the Future

Today, China ranks among the top wine-consuming countries globally, with a burgeoning domestic wine industry and a growing taste for wines from international producers.

Ties with French winemakers, particularly, have flourished, with collaborations and exchanges nurturing China’s wine culture. Regions like Ningxia have gained global recognition for their wine quality, further solidifying China’s position as an influential player in the world of wine.

In a bold prediction, wine merchant Berry Brothers and Rudd projected in 2008 that the quality of Chinese wine would rival that of Bordeaux within five decades.

Wine Regions in China

Wine culture is relatively new in China, but for a short period of time, the country grew to be the 5th largest wine consumer in the world. Here are the regions in the country where wine is largely produced:

Shandong

Yantai, located in the famed Shandong region, is the largest producer of Chinese wine. In this vibrant wine region nestled in China’s northern lands, there are over 140 wineries – contributing to a remarkable 40% of the country’s wine production.

Here, you’ll find China’s oldest and grandest winery, Changyu Pioneer Wine, with a rich history dating back to 1892. As you explore the enchanting landscapes of Yantai and Penglai, you’ll notice their unique position along the same latitude as Bordeaux, creating a striking resemblance between these two prestigious wine-growing regions.

With its warm temperate continental monsoon climate, Shandong enjoys a distinction among Northern China’s wine regions—it’s the only place where vineyards need not be buried during the winter months. As you meander through Yantai’s picturesque vineyards, you’ll be captivated by the lavish French-inspired châteaux that adorn several prominent wineries, echoing the elegance of Bordeaux.

Ningxia

Ningxia is the most famous wine-producing region in China, renowned for its exceptional wines comparable to Bordeaux blends. Located in the northwest part of China, this enchanting region boasts around 30,000 hectares of land predominantly planted with red grape varieties like Cabernet Gernischt, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Merlot. However, due to the cold climate, the vines need tender care and are laboriously buried every autumn to shield them from freezing.

In December 2011, Ningxia took center stage during the “Bordeaux against Ningxia” competition in Beijing, where experts from China and France savored five wines from each region. Surprisingly, Ningxia emerged as the clear winner, securing four out of five top spots, leaving a lasting impression on the wine world.

Ningxia’s Eastern Helan Mountain Foothills offers China’s most critically acclaimed wines, particularly in Bordeaux varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Cabernet Gernischt (Carménère). With about 93,900 acres of vineyards (38,000 hectares), Ningxia stands as the second-largest wine region in China. The region is dotted with around 200 wineries, most of which thrive on the low foothills of Helan Mountain, gracing the landscape with scenic beauty.

In 2013, Ningxia established its own classification, taking inspiration from the esteemed 1855 Classification of Bordeaux. This regional classification system undergoes revision every two years, dividing the top wineries into different “grades.” Presently, 35 wineries are honored on this esteemed list.

Hebei

Hebei is a province situated on China’s east coast, encircling the vibrant capital city, Beijing. Viticulture in Hebei finds its distinct expression in two remarkable regions: the hilly terroir of Huailai, boasting the renowned China Great Wall Wine Company, and the coastal city of Changli, affectionately known as “China’s Bordeaux region.”

Hebei proudly stands as the third-largest wine-producing region in China, nurturing 32,130 acres (13,000 hectares) of vineyards. It’s no surprise that wine is the mainstay of Hebei’s industry, commanding a market worth 10 billion Yuan (USD $1.4 billion).

Cabernet Sauvignon takes center stage in the Hebei wine industry, while smaller plantings of Chardonnay, Merlot, and Marselan also grace these fertile lands.

Xinjiang

Xinjiang is one of the country’s major sources of table grapes and wine grapes. While this breathtaking region boasts a rich agricultural history, its modern wine industry had a slow start, primarily due to its remote location, leading to higher transportation costs.

Nestled in northwest China, Xinjiang shares borders with Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan. Despite its challenging conditions with low rainfall and significant temperature fluctuations between day and night, the region remarkably produces around 100,000 tons of grapes on just 16,000 acres (6,470 hectares) annually.

The unique climate of Xinjiang yields grapes with high sugar content and low acidity, giving rise to wines with a delightful sweetness and a somewhat mellow profile. However, transport to and from this region poses considerable challenges, prompting most wines to be shipped in bulk to large wine companies for blending.

Yet, against all odds, Xinjiang holds great potential, drawing from its agricultural legacy, particularly in raisin production. Within this vast expanse, two regions stand out with geographic indications of interest: Turpan and Hoxud. Here, you’ll encounter a captivating array of wines, including Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, and Chardonnay.

Yunnan

Yunnan, the southwestern province of China, has small vineyards dispersed due to the mountainous terrain. Yunnan’s borders extend to Laos and Myanmar, so it’s an area along the tropics.

Though one might not expect quality wine to thrive in tropical climes, Yunnan defies expectations with its high-altitude Shangri-La Mountain range, soaring to 8,530 feet (2,600 meters). This elevation makes it possible to cultivate exceptional wine grapes, predominantly Cabernet and Merlot, with a touch of Chardonnay adding to the delightful mix.

In recent years, Moët Hennessy recognized the untapped potential of Yunnan’s northwestern region, Shangri-La, and made a significant investment to grow grapes organically for premium red wines. This venture encompasses 500 acres of Cabernet varieties tended to by more than 120 Tibetan farmers.