The popular American TV game show Tic-Tac-Dough was inspired by the classic tic-tac-toe board game. Participants answer questions across many topics in order to raise their team’s X or O on the board. There were three iterations of the show, with the first one airing from 1956 to 1959 on NBC, the second one running from 1978 to 1986 on CBS, and the third one being syndicated in 1990. Barry & Enright Productions was the company that was responsible for producing the program.

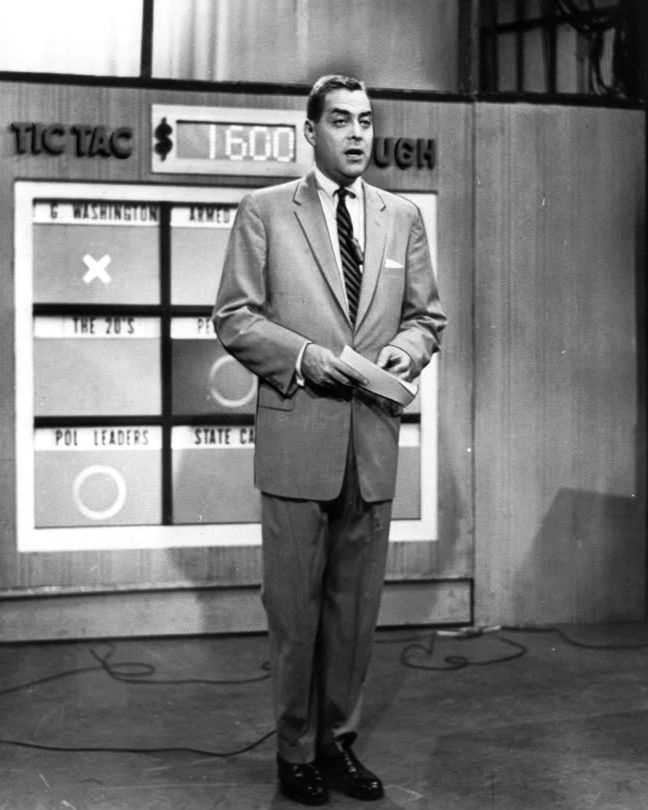

Jack Barry, who was also a co-producer of the show, was the first host of the version that aired in the 1950s. He was succeeded as host by Gene Rayburn and later Bill Wendell, with Jay Jackson and Win Elliot for prime-time adaptations. Beginning in 1978, Wink Martindale hosted the network and syndicated versions of the program. In 1985, however, Martindale departed the program to preside over and co-produce Headline Chasers, and Jim Caldwell took over as host for the remainder of that season. In 1990, Patrick Wayne served as the show’s host.

Things to Know About Tic-Tac-Dough

The original series premiered on July 30, 1956, with Barry as the quizmaster. However, there is conflicting information on the involvement of Gene Rayburn. Some sources assert that Rayburn exclusively hosted the show on Fridays until his departure in February 1957, while others claim that he assumed the role of host, succeeding Barry, sometime around April 3, 1958. Nevertheless, a nighttime version started in September 1957 with Jay Jackson as the host; unfortunately, this run was rigged almost three-quarters of the time. Both versions changed hosts in October 1958, most likely because to the escalating scandals – Jackson was replaced by Win Elliott on October 2, while the daytime emcee was replaced by Bill Wendell four days later. The daytime series ended on October 23, 1959, while the evening program was cancelled on December 29 of the same year.

CBS broadcast a daytime revival hosted by Wink Martindale from July 3 through September 1, 1978. This time, the game board consisted of nine TV screens that were linked to an Altair 8080. Additionally, the gameboards were nine Apple II computers. Two weeks following the end of its CBS run, Tic-Tac was syndicated by Colbert Television Sales with Martindale as host. The program was often shown in various cities as a 60-minute block together with The Joker’s Wild, another Barry & Enright production.

Martindale departed the program in 1985 to establish and host the syndication show Headline Chasers. In the 1985–86 season, the show’s last year, the set design changed from a woodgrain pattern to a pastel one, the logo went from yellow to blue, additional red boxes were introduced, and Jim Caldwell took over as host.

Another syndicated revival made its premiere on September 10th, 1990, this time with Patrick Wayne as the presenter and ITC Entertainment in place of Colbert Television Sales as the distributor. After just 13 weeks (although replays ran until March 8, 1991), this version was canceled on December 7 due to widespread disapproval of the alterations made. In 2021, it was stated that Tom Bergeron would host a new version, with Harry Friedman and Village Roadshow Television serving as executive producers. However, that program never went beyond the pilot stage.

Gameplay

On a typical tic-tac-toe board, the objective of the game was to be the first player to complete a line consisting of three X or O markers (the defending champion would always start with X’s and would go first). There were nine different categories shown on the gameboard. At regular intervals, competitors would choose a topic and take turns answering a question of general knowledge or trivia pertaining to that topic. If they guessed correctly, they may place an X or O on that square; otherwise, it would go unmarked.

Each contestant chose a category, and then the host asked a question from that topic. In this game, a box is won by correctly inserting one’s symbol in it, while a wrong response results in the box being unclaimed. The order of the categories was changed after each round (or turn) at first. The goal of the game was to form lines of three identical Xs or Os, either horizontally, vertically, or diagonally.

Along the way, money was added to the prize pool whenever a right answer was given. The questions in the center box were more difficult than the questions in the other boxes; in fact, all of the questions in the center box were two-parters, and the contestant in charge was given more time to ponder it through. The outside boxes were worth a little sum, but the center box was worth significantly more.

The player who obtained tic-tac-dough first won the round, earned the title of Tic-Tac-Dough champion, received the whole prize pool, and (beginning in the 1970s) proceeded to the Tic-Tac-Dough bonus round. In the event of a deadlock (eight boxes each with no possibility of winning or the board being entirely filled up), a new game would be played (with additional categories introduced in the 1970s) and the pot would continue to increase from the previous total sum from the previous game. If the challenger (“O” player) lost, they received compensation for each tie.

Before 1980, all of the categories were general information with blue backgrounds. Later, special categories were gradually introduced. The winner was then given questions based on the category he or she selected from the board. If the player is right, an X or O appears in the box, and the other player passes. Each box claimed money for the pot that the game’s winner would get. The outside boxes were valued at $200, while the middle box was valued at $300. The middle box questions were often more difficult, requiring a two-part response. The categories were swapped after the O player’s turn. Later, the categories were shuffled after each turn.

The game was over, and the pot was awarded to the player who got tic-tac-toe first. If the game was played to a draw, the money that was in the pot was carried over to the next game, which had a new set of categories on the board. For every game that ended in a draw, the loser would get $250. If the game board had a Bonus Category and maybe a Double or Nothing option, the winner might sometimes win before the opponent ever had a chance to choose a box. In such a case, the champion would be awarded the victory as usual, but the challenger would be given a second chance at a match following the conclusion of the bonus round.

Tic Tac Dough Categories

Tic-Tac-Dough is a game show modeled on the paper-and-pencil game tic-tac-toe in which contestants respond to queries in a variety of categories. After each turn or round, the categories change, and the center square typically contains a two-part question worth more money. The following is a list of some of the categories that have been used over the course of the show:

- Auction. The contestants were given a question with more than one right answer. People bid on how many right answers they could name until one of them either deferred to his opponent or chose to name all of the answers on the list. If the successful bidder met the bid, he or she won the box. If not, the other participant required just one more accurate answer to win the box.

- Bonus Category. The competitor received extra chance if they correctly answered a three-part question. Since the categories were mixed up before the bonus round, the winner might have won the game on his or her first turn simply by picking the same category over and over again. In such case, the opponent was asked to return for the following match.

- Challenge Category. The contender who chose this category had the option of answering the question or challenging their opponent to do so. Both contestants had an equal chance of winning the box with a right answer, and the person in charge also had that chance if the other person missed.

- Double-Nothing. The player might win both the box and another box on the board by responding to a random question.

- Jump-in Category. When it first started in 1983, Wink read an unbearably long question to the two contestants, and the first person to buzz in could answer. If one of the contestants missed, the other player could generally hear the rest of the question and answer.

- Number Please. Each participant was given a number question to answer. Whoever chose the category made the first guess at the answer, and their opponent made the higher or lower estimate. If the opponent was correct, they were awarded the box; otherwise, the first contestant was declared the winner. A correct estimate of the number automatically earned the box for the first contestant.

- Play or Pass. A category’s first question might be answered by the contestant, or they could skip it and go on to the next.

- Secret Category. This was the first red category on the program, and it first displayed in the bottom right corner before moving to the bottom center. The host didn’t say what the Secret Category was about until it was chosen. If you got that question right, the pot’s value doubled.

- Seesaw. Both contestants heard a question with more than one answer. Players took turns answering questions correctly until one of them made a mistake, repeated an answer, or just couldn’t come up with an answer at all; in these cases, the box went to their opponent. You could also get the box by giving the last right answer.

- Showdown. The contestants were given a question with two parts, and they were instructed to ring in using their buzzers. The first person to ring in gave an answer to part of the question. The other contestant responded second. If one contestant was correct and the other was incorrect, the contestant with the correct answer won the box. If not, more questions were asked until the winner was determined.

- Three to Win. The rules are the same as in Jump-in Challenge, except that the first person to answer three questions correctly wins the box, and all questions must be from the same category.

- Top Ten. Both players attempt to provide an answer that ranks on the list after a question is read. Whoever provided the answer with the highest ranking wins the box.

- Trivia Challenge. A question with three possible answers was asked to the participant. The competitor had the option of answering first or passing the question on to their opponent. Regardless of who began, if a contender got the answer wrong, their rival might choose from the remaining options. If the other player also got it wrong, the box remained unclaimed. During the 1984-85 season, the game was renamed Trivia Dare.

Prominent Contestants

Thom McKee

One of the best players in the history of game shows. He did very well on the competition test and beat a winner who had won more than $100,000. Thom won game after game for three months, including a five-tie game that had hit $36,800 because of the Secret Category.

Thom and his $229,600 were featured in promotions for the 1981 season of Tic Tac Dough, making viewers curious as to whether he might win $250,000 or more. Thom lost the title to Erik Kraepelien after 44 victories, eight cars, and $312,700 in cash and prizes. Erik also took home $69,000 for himself, including a $24,300 victory that was very comparable to Thom’s.

In 1983, Thom participated in the All-Time Tournament of Champions, but was eliminated in the quarterfinals after a tie game due to a loss on the Seesaw tiebreaker.

Kit Salisbury

Kit, the winner of a Florida Contestant Search, would have shattered Thom’s record for wins if not for his terrible luck in the bonus game. He won between $600 and $700 thanks to the Bonus Category and Double or Nothing. After winning more than forty games and eight cars, he ultimately earned $199,750; nevertheless, the game ended when he misspelled “misspell,”.

He was the only contestant except Thom McKee to win more money from the show.

Wrapping Up

Since the 1950s, Tic Tac Dough has been a mainstay of American television. It’s a game that requires knowledge, strategy, and above all, FUN

Tic Tac Dough produced a thrilling and tense environment for both participants and spectators by combining trivia knowledge with tactical decision-making.